Social Studies skills

Social Studies Skills

See also:

Article Objective

- conceptual tools for the Social Studies

- tools for development higher-level thought

- tools for student appreciation and engagement of Social Sciences

These tools provide the conceptual framework for understanding the Social Studies

- students may apply these tools towards any subject in the Social Studies

- >>asdf

Distinctions

- "in distinction is learning"

- a primary tool for understanding the Social Studies content is the ability to distinguish

- moving students from generalization to distinction is core goal for thoughtful approach

- student logic and writing is frequently marred by the absence of effective distinction

- examples

- "Egypt was unified because of the Nile"

- this statement makes no distinction between the Nile and other rivers, thereby it assumes that all civilizations along rivers will be unified

- >> to do>> more examples at higher levels

- "Egypt was unified because of the Nile"

Geography

Note: change to separate category and entry for Geography or leave here as a skill and add new entry /category for Human Geography

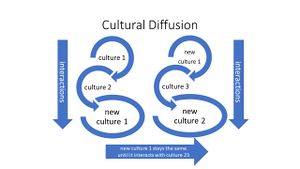

Movement

- geography shapes human interactions

- when people mix, exchange, interact, we call it "cultural diffusion"

- = the spread of ideas, languages, religions, values, cultural practices, technologies, disease, etc. through trade, migration and warfare

- see full section on Cultural Diffusion below

- geographic barriers to movement:

- inhibitors = less movement = less cultural diffusion

- types of barriers or inhibitors to movement:

- mountains, deserts, oceans & seas, crossing rivers, jungles, deserts, canyons, waterfalls (cataracts)

- long distances

- climate: extreme climates and differences in climate across regions = barrier to cultural diffusion

- geographic catalysts for movement:

- facilitators = more movement = more cultural diffusion

- facilitators = aids to movement

- types of facilitators to movement:

- valleys, going along rivers or coastlines, flat lands,

- similar climate = aid to movement

- short distances

- geographic features that can act as both barriers to and facilitators of movement :

- rivers = "both a highway and a moat"

- a coastline as both inhibitor and facilitator of movement

- woods, lakes, and rivers as

- barriers during warm weather

- and facilitators in cold weather (ice, lack of underbrush during winter, etc.)

- examples

- Wallace line see Wallacea

Isolation

- a state of geographic separation from other people and places

- isolation is caused by geographic barriers

- note that isolated areas may have isolated regions within themselves

- isolation creates regions

Regions

- definition = areas of something in common,

- defined by:

- geography/ movement, which defines:

- language, religion, culture, etc.

- political control

- regions contain sub-regions and sub-regions to that:

- USA = East coast, Midwest, West Coast, South, New England, etc.

Natural Resources

- details

Climate

- details

Causality

- study or understanding of why things happen or not

- causality can be complex and misleading

- students may evaluate causes, agents, and events for historical comprehension

- see section on agents, triggers & catalysts

- below for terms associated with causality

Correlation v. causation

- correlation = associated events, generally at or around the same time

- correlation does not mean causality

- ex. "I washed the car, so it rained the next day."

- correlation does not mean causality

- superstitions are frequently derived from a confusion between correlation and causation

- rationalization is a form of misallocation of correlation for cause:

- ex., if a student gets a low grade:

- "It's my teacher's fault" or

- "Well, I didn't have time to study, anyway"

- = placing blame on something that did not cause the outcome of the low grade

- ex., if a student gets a low grade:

Types of causes

Direct cause

- the closest cause to an event

- the cause that triggers an event

Indirect cause

- a cause that contributes to an event or outcome but is not directly related to it

- may be a "necessary clause" but not necessarily

Long term cause

- similar to a "ultimate cause," but encompassing other causes more closely related to an event or condition

Proximate cause

- same as "sufficient" cause

- especially in a legal context, identical to "sufficient cause"

- in the Social Studies, proximate causes are often confused with "short term" cause

Short or near term cause

- similar to "direct cause," but encompassing other causes more closely related to an event or condition

- synonymous with "proximate cause"

Ultimate cause

- similar to long term cause, but indicates a "necessary cause"

- i.e., it is necessary that this cause exists, but it is not "sufficient" to trigger the outcome

Causality chain

- causality can be very complex, inter-woven and inter-connected

- we can think of causality as a "chain"

Agency, catalysts, triggers & constraints

- = things that contribute to, facilitate, or make or things happen (or not)

Agent / agency

- active causes for events (or non-events)

- generally deliberate

- "agent" = someone who makes something happen, such as:

- "travel agents" make travel happen, "secret agents" make secrets/spying happen

- see "human agency" below

Catalyst

- similar to an agent but may not be deliberate

- more like a condition that creates or facilitates change

- think of use of "catalyst" in science: an element that causes a reaction

Trigger

- a specific event or condition that directly causes something to happen

- associated with "direct cause"

- not necessarily deliberate

- such as, the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand by Serbian nationalists triggered World War I"

Constraint

- whereas outcomes are shaped by agency, catalysts, and triggers,

- constraints always exist and shape outcomes

- "constraint" =

- con- (with) + *strain (bound, pulled together)

- thus "with limits"

Necessary v. sufficient causes

necessary cause

- = something that must happen in order for an event or outcome to happen...

- but the event or outcome did not have to happen because of that necessary cause

- in other words, a necessary cause does not alone make an event or outcome happen

- but the necessary cause must be present for that event or outcome to happen

- a necessary cause may exist but that does not mean the event or outcome had to happen

sufficient cause

- = something without which an event or outcome would not have happened

- in other words, the event does not happen without the sufficient cause

Necessary v. sufficient causes example

| EVENT | NECESSARY CAUSE | SUFFICIENT CAUSE |

| I mowed the lawn last Tuesday |

|

|

| goal scored in a soccer game from an assist |

|

|

Other causality terminology

Connection

Effect

collateral effect

Mono-causality v. multi-causality

- mono-causality = a single or dominant cause (simple)

- multi-causality = multiple causes (complex)

Motive

- motives are frequently behind agency, catalysts and triggers

- historical literacy is enhanced by understanding motives

Unintended consequence

- when an expected outcome yields additional, unexpected and/or unpredicted outcomes

- those outcomes may be positive or negative

- frequently historical choice is made that causes a different outcome than that expected by the actors or agents

- ex. Some French aristocrats early on supported the French Revolution but themselves became victims of it.

- a problem of the unknown unknowns

- what is expected may happen

- but the unexpected was not expected = unintended consequence

Why the cat died last night: an exercise in causality

>> to do

Contingency

- = conditions and choices

- = the idea that things didn't have to happen the way they did

"Packages"

- the conditions necessary for certain outcomes, such as

- "packages" are useful for students to understand distinctions in historical places, eras, and outcomes

- ex., the industrialization "package" of the 1870's United States included the Civil War, immigration, laissez-faire governance, plentiful resources, etc.,

- whereas the industrialization "package" of 1870s India included plentiful resources, high population, British governance and colonial resource manipulation,

- thereby India did not industrialize in the 1870s the same way as did the U.S.

- ex., the industrialization "package" of the 1870's United States included the Civil War, immigration, laissez-faire governance, plentiful resources, etc.,

Regression analysis

- contingencies can be revealed and understood by "regression analysis"

- = extracting variables to identify causality

- in the discipline of History, it is an intellectual exercise, since we can't change events

- sometimes called "counter-factual" or "historical fiction" ("what if?" type scenarios)

- however, it's illuminating to consider and evaluate different variables that create historical contingencies and actual outcomes

Path dependencies

- also called "pathway dependencies"

- using contingency, we see that set conditions define available choices

- we also see that those choices are constrained by those conditions

- i.e., an isolated agrarian society cannot simply choose to industrialize if the conditions for industrialization are not present

- that society can engage in a series of choices that might create those conditions over time

- we also see that those choices are constrained by those conditions

- however, sometimes even available choices are not present not because while those choices might seem available "path dependencies" inherently limit them

- ex., early United States could have chosen to abolish slavery as that choice was articulated and available

- however, the early US suffered from a "path dependency" in the constitutional relationship between the slave and free states that prevented that choice from being taken

- instead, the choices taken ultimate led to civil war

- path dependencies shape decisions in a form of a circular argument:

- ex., "we cannot increase food production because we don't have enough food to provide for workers to increase irrigation that would lead to higher food production"

Contingency Traps

Contingency Fallacy

- an error of historical interpretation through the lens of the present

- i.e., one's understanding of the past is shaped around conditions and perspectives that accord to the present but are not valid in interpreting the past

Contingency Trap

- by failing to consider the nature of a contemporaneous past (i.e., how and why things were at the time),

- modern points of view fail to appreciate the conditions and choices that led to their own modern, contemporaneous conditions and the choices they face.

- the "trap" occurs by negating the value of an historical moment while failing to identify that event as necessary and sufficient for the present day

- "traps" create a paradox

Dictators paradox

- from Presidnt Herbert Hoover

- "It is a paradox that every dictator has climbed to power on the ladder of free speech. Immediately on attaining power each dictator has suppressed all free speech except his own."

- the idea that

- to attain power a dictator must have access to free speech (press, publicity, etc.)

- but to maintain power, a dictator must shut down free speech (of opponents)

- an ultimate effect is that by prohibiting speech and dissent, the dictator also

- reduces access to information from which to guide policies and hold on power

- generates resentment and hostility

Grandfather paradox

- the idea that time travelers who changes the past may erase their own future lives, thus themselves

- was expressed in 1931 in a reader letter to a science fiction magazine that discussed:

"the age-old argument of preventing your birth by killing your grandparents"

Tyrants paradox

- local leaders are chosen by the dominant power

- but do not have support of local population

- as opposed to "subsidiary" = local control, which has greater access to local information

Utopia paradox

- the idea that what happened in the past could or should have been different

- the fallacy occurs from transposing (switching upon) present-day outlook upon the past

- i.e. measuring or defining the past historical values, conditions and choices with present-day values, conditions and choices

- would these historical actors be satisfied with conditions of today?

- if so, what would they have done differently

- aside from its impossibility, the Utopia paradox misunderstands history:

- by confusing what actually happened with what the observer wishes had happened

- note that study of contingency helps avoid the Utopia paradox:

- by studying conditions and choices based upon those conditions ("contingency") we can better understand both the present and past worlds

Effects

Proximate Effects

Ultimate Effects

Causal Effects

Minor Effects

Inverse Effects

Unexpected consequence

Time, change & continuity

measurement of time

- in history, time is both linear and relative

- i.e., common cycles & conditions may occur at different times in different places

- each measures itself

- peoples across history measure time via

- sun, seasons, moon cycles, weather, and leaders or dynasties

- modern measurement of time

- B.C. or B.C.E.

- A.D. or C.E.

- B.P.

Stability

- humans crave stability and predictability

- people do not like uncertainty

- religions, institutions & other social structures are designed to manage uncertainty

- societies change or don't change according to events or conditions

- agents of change include:

- cultural diffusion

- climate

- food supply (impacted by climate and cultural diffusion)

- population (impacted by food supply)

- technologies (impacted by climate and spread by cultural diffusion)

Change

Continuity

- punctuated equilibrium

- moments of rapid change

- = critical juncture

Cultural diffusion

Cultural diffusion

- the spread (diffusion) and mixing of people

- cultural diffusion operates through:

- trade, migration & warfare

- cultural diffusion spreads or mixes:

- culture, disease, race, religion, identity, technology, etc.

Cultural diffusion: movement, change & assimilation

- cultural diffusion causes change

- cultural diffusion occurs when people of one place interact with another

- in fact, people in any given "place" are the result of prior episodes (events, processes) of cultural diffusion

- the more movement in a region, the more that region

Geography & cultural diffusion

- isolation

- crossroads

- rivers as both "a highway and a moat"

- see geographic barriers: inhibitors to movement

- see geographic catalysts: facilitators to movement

- spreads more readily across similar climates and latitudes (east - west)

- rather than across different climates (north - south)

- spreads more readily across similar climates and latitudes (east - west)

Technology & cultural diffusion

- boats

- bridges

- horses

- mechanized transit, including

- automobiles

- railroads

- steamboats

- telegraph / telephone

- rails (pre-steam)

- radio / TV

- roads

- writing

- See also

Historical technological advance that enhanced cultural diffusion

Writing

Hammurabi's Code

Telegraph, Radio & TV

- 1909: President Taft using telegraph to launch NYC automobile race

- 1922: President Harding gave the first presidential address via radio

- Harding's dedication to a Baltimore memorial to Francis Scott Key was broadcast via radio

Historical technological advance that enhanced cultural diffusion

Writing =

Hammurabi's Code

Telegraph, Radio & TV

- 1909: President Taft using telegraph to launch NYC automobile race

- 1922: President Harding gave the first presidential address via radio

- Harding's dedication to a Baltimore memorial to Francis Scott Key was broadcast via radio

Cultural diffusion as historical agent

- mixing of cultures, technologies, language, relgion, etc.

- Do the conquerors conquer the conquered or do the conquered conquer the conquerors?, examples:

- Mongol conquerors of China became Chinese (Yuan Empire)

- Turk invaders of Anatolia became Muslim

- Norman invaders of England became English

- Ptolemaic (Greek) rulers of Egypt

Comparison

Sub Heading

Distribution of Power

- a measurement of how societies "distribute" or organize sources and applications of power

- "power" may be considered any application of force or coercion or structure that achieves the same

- examples,

- policing = power to enforce laws

- a state religion would create a possibly coercive structure to which members of that society belong

- "narrow distribution" of power = centralized governance

- may include

- monarchy, tyranny, totatalitarian, etc.

- may include

"wide distribution" of power = decentralized governance

- may include:

- democracy, anarchy

- no society is all one or the other

- even anarchy essentially distributes power to the individual level, which may be coercive at that level

- even a totalitarian society may allow for family units which govern themselves or religious freedoms

Social organization

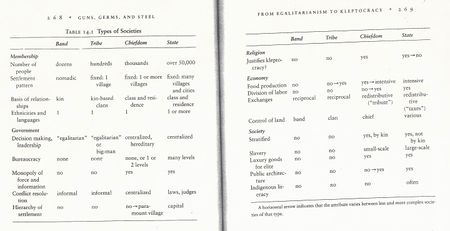

- In "Guns, Germs & Steel," Jared Diamond analyzed social organization by type and characteristics

- his chart serves a very useful comparative tool

- especially for measuring social organization over time and place

- Dunbar's number:

"Dunbar's number is a suggested cognitive limit to the number of people with whom one can maintain stable social relationships—relationships in which an individual knows who each person is and how each person relates to every other person" from [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dunbar%27s_number Dunbar's Number (wiki)]]

Revolution paradox

- Tocqueville observed "that the most dangerous time for a bad government is usually when it begins to reform."

- from "The Old Regime and the Revolution" (1856)

- see below for the "Tocqueville effect"

Thucydides Trap

Tocqueville effect

- or "Tocqueveill paradox"

- Alexis de Tocqueville noted that

"The hatred that men bear to privilege increases in proportion as privileges become fewer and less considerable, so that democratic passions would seem to burn most fiercely just when they have least fuel. I have already given the reason for this phenomenon. When all conditions are unequal, no inequality is so great as to offend the eye, whereas the slightest dissimilarity is odious in the midst of general uniformity; the more complete this uniformity is, the more insupportable the sight of such a difference becomes. Hence it is natural that the love of equality should constantly increase together with equality itself, and that it should grow by what it feeds on." - Tocqueville, Alexis de (1840). "Chapter III: That the sentiments of democratic nations accord with their opinions in leading them to concentrate political power". Democracy in America

>> todo: bring in Mancur Olson and Theory of Groups >> see wiki entry Mancur Olson about how interests tend to coalesce over time and focus on protection of gains, stifling innovation... organizations become "congealed" (from("How Phil Falcone Was LightSnared" WSJ, Homlan W. Jenkins, Jr. 2/18/2012") and resist competition and protect the status quo

Order & Chaos

- see below for certainty v uncertainty

- order = certainty

- chaos = uncertainty

Order

- social structures are primarily designed to bring stability to human interactions

- order advantages

- stability

- predictability

- especially for commerce, food supply, peaceful existence

- order disadvantages:

- inequities inherent in any large social structure

- inability to self-correct

- consequences of too much order:

- lack of feedback and information

- dissolution and atrophy

- systems decline, can't adjust to change

- may lead to unintended negative consequences

Chaos

- chaos is either cause or effect of change

- chaos as "change agent"

- benefits of chaos:

- correction

- challenging inequities or inefficiencies in an overly-structured system

ideal balance of order & chaos

- healthy systems combine elements of both

- creating predictability and stability

- while mitigating harms of overly structured system

- creating predictability and stability

- feedback and self-adjustment without a need for drastic change

- Thomas Jefferson idea of generational revolution

- Jefferson believed that each generation required a renewal from the prior

>> source to do

Certainty v. Uncertainty

- humans dislike change

- humans fear the unknown

- humans yearn for predictability

- see Thomas Hobbes' "Leviathan" for analysis of human fear of uncertainty

Click EXPAND for excerpts from Leviathan on uncertainty:

Only the present has an existence in nature; things past exist in the memory only; and future things don’t exist at all, because the future is just a fiction of the mind, arrived at by noting the consequences that have ensued from past actions and assuming that similar present actions will have similar consequences (an assumption that pushes us forward into the supposed future). This kind of extrapolation is done the most securely by the person who has the most experience, but even then not with complete security. And though it is called ‘prudence’ when the outcome is as we expected, it is in its own nature a mere presumption.

from Leviathan, Chapter 3, "Train of Imaginations" and

Anxiety regarding the future inclines men to investigate the causes of things; because knowledge of causes enables men to make a better job of managing the present to their best advantage. Curiosity, or love of the knowledge of causes, draws a man from consideration of the effect to seek the cause, and then for the cause of that cause, and so on backwards until finally he is forced to have the thought that there is some cause that had no previous cause, but is eternal; this being what men call ‘God’.

from Leviathan, Chapter 11, "The Difference of Manners"

Calendar & Astrology

- tracking time, seasons, and years brought stability and predictability

- especially for seasonally dependent activities such as trade, farming, and warfare

- Astrology, or the study of the position of the stars

- = method of tracking time and seasons

- led to advances in navigation and mathematics

- see below for importance of the Winter Soltice

Divine intervention & explanations for events

- the Winter Solstice (Dec 21/22) marks the sun's lowest trajectory in the northern hemisphere

- why is this important?

- that the sun has descended and that it will commence its rise again to higher points in the sky

- = rebirth, a new start = celebration and deep life-cycle significance

- why is this important?

- At the Battle of Marathon (Greeks v. Persians), the Athenian commander (War Archon) Callimachus promised to sacrifice a kid (baby goat) to the goddess of the hunt, Artemis. Having killed 6,400 Persians, the Athenians had to kill 500 goats a year in her honor for more than a decade. (source: "The Greco-Persian Wars" by Peter Green; p. 32)

- after losing ships to a storm prior to the battle of Thermopylae, Persian king Xerxes ordered his Magi to placate the weather with offerings and spells; the storm subsided

- Herodotus, the first Greek historian, noted, "or, of course, it may just be that the wind dropped naturally" ("The Greco-Persian Wars" by Peter Green; p. 124)

- Babylonian king Hammurabi wrote on Hammurabi's Code that the laws were given to him by his gods in order to protect the people he ruled (divine justification)

- in ancient world outcomes were explained by divine intervention

- victors in war or power struggles were thought to have been selected by gods (divine choice)

Legitimacy

- favorable outcomes = divinely determined = therefore divinely chosen = legitimacy of outcomes

- unfavorable outcomes = loss of legitimacy

- examples

- break-down of Old Kingdom pharaonic rule in Egypt following reduced flooding of the Nile

- pharaohs lost legitimacy and social, political, and religious rules were freely broken as result of widespread famine and social collapse

- Xerxes punishes the Hellespont for disobeying him

- after a storm wrecked his boat-bridge across the Hellespont, Xerxes ordered soldiers to whip its surface in punishment for insubordination

- break-down of Old Kingdom pharaonic rule in Egypt following reduced flooding of the Nile

Ritual

- to bring certainty to uncertain events

- to bring order and predictability

- rituals can:

- appeal to god(s) for desired outcome

- predetermine events by acting them out "ritualistically" (such as a hunt)

- superstitions mitigate uncertainty

risk v. reward

- social choices

- social organization

- unintended consequences

- opportunity costs

- comparative advantage

- examples:

- farming v. hunting gathering

- war: Pyrrus v. the Romans

- examples:

- conditions v. choice

Unity / disunity

- << move to order/chaos above

- unity can formed or defined by

- power/ force

- homogeneity

- same language, religion, ethnicity, etc.

- geographic isolation

- drives homogeneity

- crisis

- disunity

- agents of unity

- agents of disunity

- dissent

- heterodoxy / nonconformity

Food <<>> Population Cycle

- in agrarian societies, the relationship between food production and population

- in industrial societies, the relationshiop between labor and economic output

- in post-industrial societies, the demographic strain of aging, population static societies

Objective v. Subjective

Scarcity & Surplus

- scarcity = state of not having enough

- generally regards food supply

- condition of scarcity

- impact of scarcity

- competition over resources / food supplies

- population growth limited to available food supply

- surplus = state of having more then enough

- generally regards food supply

- condition of scarcity

- impact of surplus

- population growth

- trade

- social stratification

- balanced food supply

- self-sufficiency = state of having just enough food / resources

- stable food supply

- hunter-gatherers can be seen to maintain a balanced food supply

- nomadic lifestyle = to maintain food supply by following/ finding food sources

- in ideal state maintain balanced food supply for stable population

- nomadic lifestyle = to maintain food supply by following/ finding food sources

- sources:

Identity

- details

- sources:

Literature & Arts

- links

Architecture

Social, Political and Economic Structures

Government

Economy

Social Structures

- social classes

- identity

- religion

- family

- gender

- citizenship v. subject

- sources:

Political Efficacy

- concept

- definitions

- internal

- external

- utility

- Machiavelli on the political efficacy from "Discourses on Livy":

- NOTE: Machiavelli did not use this term

"Whoever undertakes to govern a people under the form of either republic or monarchy, without making sure of those who are opposed to this new order of things, establishes a government of very brief duration. It is true that I regard as unfortunate those princes who, to assure their government to which the mass of the people is hostile, are obliged to resort to extraordinary measures; for he who has but a few enemies can easily make sure of them without great scandal, but he who has the masses hostile to him can never make sure of them, and the more cruelty he employs the feebler will his authority become; so that his best remedy is to try and secure the good will of the people."

- Source: Machiavelli, Niccolo; Burnham, James; Detmold, Christian E. (2010-11-25). Discourses on Livy (with a study by James Burnham) by Niccolo Machiavelli, Christian E. Detmold, James Burnham.

- select expand to see quotation

Human agency & leadership

- an element of contingency, choice, represents "human agency"

- "agent" = a causal element, i.e., that makes things happen

- thus "human agency" = the choice and actions of people in historical events and outcomes

- while organizations, conditions, structures, geography, etc. largely shape historical conditions and outcomes

- human agency, or choice and actions, is how history happens

- thus "leadership" is as important as structures

- however, human agency is limited by available choice

- i.e., leaders of an inland country, say Mongolia, will not likely choose or be able to create a maritime empire

- instead, effective leadership did organize Mongolia into a land-based empire using existing structural elements of Mongolian geography, economy, and culture

- then, using that land-based power, the Mongols conquered China, established the Yuan Dynasty, and used Chinese structures and culture to build a maritime power.

- i.e., leaders of an inland country, say Mongolia, will not likely choose or be able to create a maritime empire

- however, human agency is limited by available choice

- see Leadership entry

Economics

Comparative Advantage

- Definition: A particular economic advantage, resource or ability a country possesses over either its own other economic situations or those of another country.

- the term "comparative advantage" was

- origin of the idea:

- late 1700s Scottish philosopher Adam Smith (1723-1790)

click EXPAND for Adam Smith quotation on "absolute advantage":

''If a foreign country can supply us with a commodity cheaper than we ourselves can make it, better buy it off them with some part of the produce of our own industry employed in a way in which we have some advantage. The general industry of the country, being always in proportion to the capital which employs it, will not thereby be diminished ... but only left to find out the way in which it can be employed with the greatest advantage.'' (Book IV, Section ii, 12)

- Comparative advantage means concentrating on what your country is good at making/doing in order to get what other countries are better at making/doing."

- early 19th century British economist David Ricardo (1772-1823):

- argued for specialization as basis for national wealth and increased trade

- = laissez-faire, free-trade

- related comparative advantage to the concept of "opportunity cost"

- i.e. what is lost by not engaging in an activity

- Ricardo argued that it would be more costly to for country A to attempt to produce something that country B can more efficiently create than to focus on what that country A itself does better (its comparative advantage) and simply purchase the other goods from country B

- and by doing so, both country A and B will benefit from the trade

- early 19th century British economist David Ricardo (1772-1823):

click EXPAND for David Ricardo's quotation on comparative advantage:

it would undoubtedly be advantageous to the capitalists [and consumers] of England… [that] the wine and cloth should both be made in Portugal [and that] the capital and labour of England employed in making cloth should be removed to Portugal for that purpose.

- British colonizer of Australia and economist Robert Torrens independently developed the idea of comparative advantage

click EXPAND for Robert Torrens' quotation on comparative advantage from 1808:

''if I wish to know the extent of the advantage, which arises to England, from her giving France a hundred pounds of broadcloth, in exchange for a hundred pounds of lace, I take the quantity of lace which she has acquired by this transaction, and compare it with the quantity which she might, at the same expense of labour and capital, have acquired by manufacturing it at home. The lace that remains, beyond what the labour and capital employed on the cloth, might have fabricated at home, is the amount of the advantage which England derives from the exchange.''

- Examples:

- Is it advantageous for the U.S. to import oil from Saudi Arabia or to rely only on its own oil production?

- see also

Economies of scale

- definition: lower costs of production based upon higher volume

- i.e., the larger the production facility, the cheaper it costs to produce any single item

- economies of scale result from:

- greater efficiency in higher production rates

- greater purchasing power to lower costs of supplies and materials

- lower per capita labor cost per cost of unit produced

Opportunity Cost

- definition: The value of the next best choice one had when making a decision.

- i.e., the trade-off of a decision.

- Opportunity cost is a way of measuring your decisions: if I do this, would having done something else been more or less expensive? What did I give up in my decision?

- Frederic Bastiat developed the "Parable of the broken window" to express the concept

- known as the "Broken Window Fallacy*" or the "Glazier's Fallacy"

- (* not to be confused with "Broken Windows Theory")

- from his essay, "Ce qu'on voit et ce qu'on ne voit pas" ("What is seen and what is not seen")

- the parable discusses the "unseen" costs of fixing a broken window

- even though the broken window provides benefit to a "glazier" makes money fixing it

- the shopkeeper suffers the "unseen" costs of not being to do something else with that money

- additionally, the opportunities to fix broken windows may create an "unintended consequence" of a "perverse incentive" for glaziers to go about breaking windows in order to make money fixing them

- known as the "Broken Window Fallacy*" or the "Glazier's Fallacy"

click EXPAND for a review of Bastiat's theory of "opportunity cost" and associated concepts of "unintended consequences" and "perverse incentives"

- Parable of the broken window

- a shopkeeper has a careless son breaks a window

- his neighbors argue that broken windows keep "glaziers" (window-makers) in business

- if it costs 6 francs to fix, they argue, the money spent on the window is productive, as it goes to the glaziers

- Bastiat replies that, yes, money has thus circulated, but "it takes no account of what is not seen" (ce qu'on ne voit pas)

- the shopkeeper can't spend those 6 francs on something else of his choosing

- or, perhaps, he has another need for 6 francs that he can not now fix

- therefore the accident of the broken window prevents the shopkeeper from using his money more efficiently

- his neighbors argue that broken windows keep "glaziers" (window-makers) in business

- Bastiat writes, "Society loses the value of things which are uselessly destroyed"

- the parable also develops "the law of unintended consequences"

- ex.: if the glaziers figure out they can pay a boy 1 franc to break windows, and they can still make a profit at 5 francs per window,

- there will thereby exist a "perverse" incentive to break windows

- "perverse incentive" = an incentive that produces a negative outcome

- there will thereby exist a "perverse" incentive to break windows

- ex.: if the glaziers figure out they can pay a boy 1 franc to break windows, and they can still make a profit at 5 francs per window,

- economists have argued over the "opportunity costs" of damaging events:

- disasters (hurricanes, earthquakes which require repair and thus create jobs & economic activity)

- wars (spur economic activity and mobilization)

- however, whatever the benefit it does not account for Bastiat's "unseen" costs and cannot in any way outweigh the suffering, death and loss of choice created by the disaster or war

- a shopkeeper has a careless son breaks a window

- see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parable_of_the_broken_window#Parable

- Examples:

- If you own land on an urban road, and you decide to build condos on it, what else might you have done, and what would that have cost -- or earned -- for you?

- Questions:

- If the U.S. imports oil from Saudi Arabia, is the U.S. giving up the potential of its own oil industry?

- If Saudi Arabia relies on oil, what is the cost of that reliance?

Herbert Stein's Law

- "If something cannot go on forever, it will stop"

- in economics and history, this concept is important for students to appreciate

- cycles

- non-linear paths of events

- change

- Herbert Stein's Law may serve as a good discussion point for evaluating choices in history

- example: why did such-and-such policy fail over time?

- source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herbert_Stein

Jevons Paradox

- also called "Jevon's effect"

- law that states that increases in efficiencies lead to more and not less use of a resource

- also: greater efficiencies lowers cost, which increases demand

- from William Stanley Jevons who in 1865 noticed that more efficiencies in coal-power generation led to more use of coal

- see Jevons paradox

- interesting historical tool

- controversial in the 2000s regarding energy use

- see New Yorker article on subject Dec/ 2010 >> to confirm

- controversial in the 2000s regarding energy use

Milton Friedman's "Four ways to spend money"

- late 20th century Economist Milton famously defined the "Four ways to spend money" (paraphrased, not original quotation):

- You spend your money on yourself

- You spend someone else's money on yourself

- Someone else spends their money on on you

- Someone else spends someone else's money on someone else

click EXPAND to see the implications of the Four ways to spend money

• Table format

| Whose money is spent by whom | Money is spent on whom | Efficiency of Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| You spend your money... | on yourself |

|

| You spend someone else's money... | on yourself |

|

| Someone spends their money... | on you |

|

| Someone else spends someone else's money... | on someone else |

|

Pareto Principle

- also known as the "80/20 rule" or "law of the vital few"

- = the idea that 80% of consequences come from 20% of causes

- the early Italian economist Vilfredo Pareto observed that

- in Italy 80% of the land was owned by 20% of the population

- other observers have found that many natural and human systems follow this distribution pattern

Other useful Economics and "Political Economy/-ics" terms and concepts

- 80/20 rule (see the "Pareto Principle" above)

- diminishing returns

- emergent order

- Broken window fallacy (also "Glazier's fallacy)

- see Frederic Bastiat's ""Ce qu'on voit et ce qu'on ne voit pas" ("That Which We See and That Which We Do Not See"): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parable_of_the_broken_window

- client politics

- externalities

- Inflation/ deflation

- Labor supply / flexibility of labor supply

- public goods

- regulatory capture

- rent seeking

- using government rules or law in order to reduce competition

- see Frederic Bastiat's "Economic Sophisms" for a satire on candlestick makers who petitioned the government to ban the sun as an unfair competitor'

- regression to the mean (return to the mean)

- risk mitigation

- scarcity v. surplus

- sunk cost / "sunk cost fallacy"

- Third-party payer effect

- when a third-party pays for goods or services, quality goes down and prices go up

- see Milton Friedman's "Four ways to spend money"

- top-down v. bottom-up

- trickle-down theory

- the idea that economic benefits conferred or made available to the top of society will "trickle down" to the rest of society

- has been attributed to "Reaganomics"

- but only by its critics, not its proponents

- in other words, "trickle down" theory is an economic criticism and not a proposition

- "trickle down" theory originated in William Jennings Bryan's 1896 "Cross of God Speech"

click EXPAND for quotation from Bryan's Cross of Gold speech that expressed "trickle down theory"

There are two ideas of government. There are those who believe that if you will only legislate to make the well-to-do prosperous, their prosperity will leak through on those below. The Democratic idea, however, has been that if you legislate to make the masses prosperous, their prosperity will find its way up through every class which rests upon them.

- Tragedy of the Commons

- zero sum transaction

- both sides of transaction receive equal benefit

- i.e., the buyer and the seller gain equal value

- thus the "sum" of the transaction is "zero"

- both sides of transaction receive equal benefit

Logic and observational fallacies

Benchmark fallacy

- a logical or statistical fallacy that measures incompatible data or other comparison point ("benchmark")

- examples:

- using a date of reference (benchmark) in order to hide a statistical trend from its true nature

- also called "cherry-picking" of dates or data

- commonly used by stock market observers in order to exaggerate or minimize the extent of a stock's rise or fall

- commonly used by politicians to make claims for or against themselves or opponents, such as:

- using a date of reference (benchmark) in order to hide a statistical trend from its true nature

click EXPAND for an example of a benchmark fallacy

Example:

| 2000 | 2006 | 2009 | 2015 | 2021 |

| 1.65 mm | 2.25mm | 0.50 mm | 1.2mm | 1.7 mm |

- mm = millions

- numbers are approximate

- benchmark fallacies using this data might include:

- a politician wanting to exaggerate a decline in housing starts might select 2005 as the benchmark date for 2021 rates (thus 2021 would have a lower rate of housing starts than 2005); conversely,

- a politician wanting to exaggerate a rise in housing starts might select 2009 as the benchmark date for 2021 rates (thus 2021 would have a higher rate of housing starts than 2009)

confirmation bias

- drawing a conclusion not from evidence but from what one wants to observe

- seeing only what you want to see

- confirmation bias impacts all areas of human thought, including

- scientists who ignore or deny contrary evidence

- politicians who take only one side of a political question even against evidence that negates it

- historians who are biased toward certain historical outcomes

- origins of the idea of confirmation bias

- Aesop's fable: Fox and the Grapes, which is where we get the expression, "sour grapes" ("oh well, those grapes are probably sour")

- examples of confirmation bias

- The New Testament tells of various miracles performed by Jesus, some of which occur on the sabbath, which is the Hebrew "day of rest" (no work is allowed)

- when some of the Jewish leaders, "Pharisees," witness a miracle, instead of responding in awe of it (such as healing a cripple or giving sight to a blind man), they become upset that Jesus performed the miracle on the sabbath

- basically, saying, "Yeah, whatever, you healed a dude, but you can't do that on a Saturday!"

- the bias of the Pharisees was so strong that they ignored the miracle and instead accused Jesus of breaking the law by "working" on the sabbath

- David Hume

- 18th century Scottish philosopher who argued that knowledge is derived from experience (called "empiricism")

- however, Hume warned against reason alone as the basis for knowledge, as one can "reason" just about anything

- Hume wrote, “Tis not contrary to reason to prefer the destruction of the whole world to the scratching of my finger.”

- Hume warned against jumping to conclusions based on limited knowledge

- i.e. drawing conclusions based on our own confirmation bias

Heinlein's Razor

- “Never assume malice when incompetence will do”

- from wiki: A similar quotation appears in Robert A. Heinlein's 1941 short story "Logic of Empire" ("You have attributed conditions to villainy that simply result from stupidity"); this was noticed in 1996 (five years before Bigler identified the Robert J. Hanlon citation) and first referenced in version 4.0.0 of the Jargon File,[3] with speculation that Hanlon's Razor might be a corruption of "Heinlein's Razor". "Heinlein's Razor" has since been defined as variations on Never attribute to malice that which can be adequately explained by stupidity, but don't rule out malice.[4] Yet another similar epigram ("Never ascribe to malice that which is adequately explained by incompetence") has been widely attributed to Napoleon Bonaparte.[5] Another similar quote appears in Goethe's The Sorrows of Young Werther (1774): "...misunderstandings and neglect create more confusion in this world than trickery and malice. At any rate, the last two are certainly much less frequent."

necessary and sufficient conditions

- necessary conditions

- = without which something is not true

- example: "John is a batchelor" informs us that John is a male, unmarried, and an adult

- = without which something is not true

- sufficient conditions

- = condition is sufficient to prove something is true

- however, sufficiency does not exclude other conclusions

- example: "John is a bachelor" is sufficient evidence to know that he is a male

normalcy bias

- a bias towards continuation of what is or has normally been

- given absence of change, a normalcy bias is accurate

- only it's accurate until it's not

- we can see across history when civilizations, peoples, or leaders counted on things "staying the same"

- consequences can be

- catastrophic systemic breakdown without preparation for change

- examples include, Ancient Egypt, Roman Empire, various Chinese dynasties

- lack of social, economic, cultural, and technological advance

- which unto itself becomes a source of breakdown, esp. vis-a-vis competitive societies

- see "stability v. change" above

- catastrophic systemic breakdown without preparation for change

- consequences can be

Occam's Razor

- original latin = lex parsimoniae

- = the law of parsimony, economy or succinctness

- = idea that the simplest explanation is most often the best

- = best solution or option is that which assumes the least variables or assumptions

- origin

- William of Ockham (c. 1285–1349) English Franciscan friar and logician

- practiced economy in logic

- "entities must not be multiplied beyond necessity"

- William of Ockham (c. 1285–1349) English Franciscan friar and logician

- term "Occam's Razor" developed later

- "razor" = knife to cut away unnecessary assumptions

- Occam's razor for students:

- to evaluate opposing theories

- to develop own theories

- to evaluate Myths & Conspiracies outline

- to develop logical thought

- see also sufficiency in logic

- note: Occam's Razor has been used by philosophers to deny any explanations that include God or religion (see "Blame it on Calvin & Luther," by Barton Swaim, Wall Street Journal, Jan 14, 2012)

Sutton's law

- from the bank robber Willie Sutton who, when asked why he robbed banks

- he replied, "Because that's where the money is."

- Willie Sutton denied ever having said that, but affirmed that he "probably" would have if someone asked him

- he replied, "Because that's where the money is."

- = seek first the most obvious answer first

- used in Medical school to teach students best practices on diagnosis and testing

Zebra rule

- "When you hear hoofbeats behind you, don't expect to see a zebra"

- similar to Sutton's law that the most obvious answer is likely correct

- used by medical schools to teach focus on the most obvious patient conditions/ illness causes

Logical fallacies and tricks

- begging the question

- broken leg fallacy

- presents a solution for a problem caused by that or a related solution

- i.e, break the leg, then offer to fix it

- confusing credentials for evidence

- i.e., "98% of dentists recommend flossing"

- does not provide evidence for the benefits of flossing, just that supposed experts say so

- i.e., "98% of dentists recommend flossing"

- fallacy of relevance

- ignoratio elenchi an argument that misses the point

- non sequitur

- " Humpty Dumptying" or "Humpty Dumptyisms":

- = an "arbitrary redefinition" like that used by Humpty Dumpty in "Alice in Wonderland"

- who tells Alice, "“When I use a word it means just what I choose it to mean—neither more nor less.”

- red herring

- strawman fallacy

- = the target of an argument (the "strawman") has nothing to do with the actual argument

- either-or fallacy

- incorrectly argues only two options or possibilities

- see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_fallacies

Kafka Trap

- a logical trap whereby the argument uses its own refutation as evidence of a fallacy

- i.e., "because you deny it, it must be true"

- the term refers to the dystopian novel by Franz Kafka "The Trial," in which a man's denial of a charge was used as evidence of his guilt

- the "Kafka trap" was coined by Eric Raymond as "Kafkatrapping" in 2010 article

Leading questions and question traps

- questions that assume an answer ("leading") or are designed to "trap" an answer

- similar to the Kafka trap

- leading questions are used in order to guide

- Socrates engaged in "leading questions" in order to make his point

- see [Socratic questioning (wikipedia)]

- and the story of the Slave Boy and the Square from Plato's Meno

- Socrates engaged in "leading questions" in order to make his point

Motte and Bailey Doctrine

- or the "Motte and Bailey fallacy"

- a fallacy of exaggeration in which an argument is presented with absurd exaggerations ("the Motte") and if objected to is replaced by an undoubtedly true but hardly controversial statement ("the Bailey", which is then used to advance the original exaggerated claim

click EXPAND for more on Motte and Bailey Doctrine:

- the term refers to a protected medieval castle and nearby indefensible village

- the Motte is the defensible, protected tower but is not appealing to live in (built on a mound or "motte")

- the Bailey is an appealing place to live but cannot be defended

- if attacked, the occupants of the retreat to the Motte for safety

- thus the exaggerated and fallacious (untrue) argument appears more reasonable

- the Motte and Bailey Doctrine frequently employs

- "strawman fallacy"

- Humpty Dumptying

- "either-or" fallacy

- "red herring" fallacy

click EXPAND for an example of a Motte and Bailey fallacy regarding a gun control debate:

Person A. "Guns don't kill people, people do" (the Bailey) Person B. "But that won't stop people from using guns to kill people." Person A. "Yeah, but guns are legal" (the Motte) Person A has conflated (confused or joined illogically) the legality of guns with their use.

or on the opposite side:

Person A. "Gun control keeps criminals from committing crimes with guns" (the Bailey) Person B. "But criminals commit crimes and won't obey gun control laws." Person A. "Either way, it's bad when guns are used to murder people." (the Motte)

- term coined by [https://philpapers.org/archive/SHATVO-2.pdf Prof. Nicholas Shackel in the paper, The Vacuity of Postmodernist

Methodology] click EXPAND for excerpt from Shackel explaining the Motte and Bailey Doctrine:

A Troll’s Truism is a mildly ambiguous statement by which an exciting falsehood may trade on a trivial truth .... Troll’s Truisms are used to insinuate an exciting falsehood, which is a desired doctrine, yet permit retreat to the trivial truth when pressed by an opponent. In so doing they exhibit a property which makes them the simplest possible case of what I shall call a Motte and Bailey Doctrine (since a doctrine can single belief or an entire body of beliefs.) A Motte and Bailey castle is a medieval system of defence in which a stone tower on a mound (the Motte) is surrounded by an area of land (the Bailey) which in turn is encompassed by some sort of a barrier such as a ditch. Being dark and dank, the Motte is not a habitation of choice. The only reason for its existence is the desirability of the Bailey, which the combination of the Motte and ditch makes relatively easy to retain despite attack by marauders. When only lightly pressed, the ditch makes small numbers of attackers easy to defeat as they struggle across it: when heavily pressed the ditch is not defensible and so neither is the Bailey. Rather one retreats to the insalubrious but defensible, perhaps impregnable, Motte. Eventually the marauders give up, when one is well placed to reoccupy desirable land. For my purposes the desirable but only lightly defensible territory of the Motte and Bailey castle, that is to say, the Bailey, represents a philosophical doctrine or position with similar properties: desirable to its proponent but only lightly defensible. The Motte is the defensible but undesired position to which one retreats when hard pressed.

Ethics

Aristotle

- by Aristotle's view, the study of ethics is essential to understanding the world around us and for finding virtue and happiness

- ethikē = ethics

- aretē = virtue or excellence

- phronesis = practical or ethical wisdom

- eudaimonia = "good state" or happiness

- steps to become a virtuous person:

- 1. practicing righteous actions guided by a teacher leads to righteous habits

- 2. righteous habits leads to good character by which righteous actions are willful

- 3. good character leads to eudaimonia

ethical dilemmas

the "Trolley problem"

- a dilemma created by the need to sacrifice one innocent person to save (usually given as) five others

- scenario:

- a runaway (out of control) trolley is heading towards a track with five workers on it (or sometimes presented as five people tied up and who are unable to move)

- there is a secondary track that was not in the original pathway of the trolley and that has one person on it

- an engineer who sees the situation can divert the trolley to the secondary track, thus killing the one person on it but saving the five on the original track

- the problem is that that one person was otherwise not in danger and not wrongfully on the track

- is that sacrifice ethical?

- the "utilitarian" view holds that it would be ethical and morally responsible to divert the trolley as it would save more lives

- by "utilitarian" we mean a choice or action that benefits the most people, even at the expense of some others

- i.e. "maximize utility"

- by "utilitarian" we mean a choice or action that benefits the most people, even at the expense of some others

- objections to the utilitarian response include:

- the engineer had no intention to harm the five but by diverting the trolley would have made a willful decision to kill the one; therefore the act would be morally objectionable

- = deliberately harming anyone for any reason is morally wrong

- = violating the "doctrine of double effect," which states that deliberately causing harm, even for a good cause, is wrong

- the engineer had no intention to harm the five but by diverting the trolley would have made a willful decision to kill the one; therefore the act would be morally objectionable

- the Trolley problem shows up in other situations:

- artificial intelligence, such as driverless vehicles

- Isaac Asimov explored moral and ethical dilemmas regarding artificial intelligence in his collection of essays, "I Robot."

- Asimov envisioned the Three Laws of Robotics

click EXPAND to read the Three Laws of Robotics

First Law A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm. Second Law A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law. Third Law A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

Standards/ Standardization

standard meaning

- standard (noun) =

- a baseline rule or line of common agreement

- i.e., what a society agrees upon as commonly expected

- etymology (word origin):

- from Old French estandardfor fpr "to stand hard", as in fixed

- derived from Latin extendere" for "to extend" and applied to an "upright pole"

- applied to a flag, a "standard" represents an army or people

- a baseline rule or line of common agreement

- standardize (verb)

- means to make in common or in common agreement

- standardization (noun) = in the state of being standardized; action of creating common agreement

purpose of standardization

- standards are a key element of creating rule, sovereignty and/or unity

- especially across large distances

- when a people agree upon something, it is "standard"

- forms of standardization include:0

- language, laws, money, religion, social customs, weights and measures, writing

- effects of standardization include:

- economic activity (trade), social and political organization, unity

- rule, power, especially in the sense of enforcing standards

- the below will review these different forms and purposes of standards and standardization

law

money

- “Money can be anything that the parties agree is tradable” (Wikipedia)

notes to do:

- money & trade

- trade =

- geography

- movement

- scarcity/surplus

- technology

- technological and cultural diffusion

- trade =

history of money

- “I understand the history of money. When I get some, it's soon history.”

- money must be:

- scarce

- too much money reduces its value

- inflation results from oversupply of money

- or corruption or devaluation of money

- see Latin expression: void ab initio

- = fraud from the beginning taints everything the follows

- transportable

- ex. Micronesians used a currency of large limestone coins...9-12ft diameter, several tons... put them outside the houses.. great prestige... but they weren’t transportable, so tokens were created to represent them, or parts of them... Tokens = promises

- authentic

- not easily counterfeited (fraudulently copied)

- trusted

- government sanction

- permanent

- problem with barter of plants and animals is perishability

- i.e., fruit and goats can be traded, but fruit goes bad and goats die

- problem with barter of plants and animals is perishability

- scarce

- early non-coinage forms of money:

- sea shells

- which are scarce (rare), authentic, visually attractive (pretty)

- cattle

- crops/ herbs/ spices

- especially specialty crops, such as spices

- such as pepper, which is dried and therefore transportable and non-perishable

- especially specialty crops, such as spices

- gems, gold, rare minerals

- measured by weight

- sea shells

- modern period money forms:

- during Age of Discovery (15th-17th centuries) rum became currency

- 18th century Virginia, tobacco became money

- in prisons or prisoner of war camps, cigarettes have become currency,

history of Coinage

- starts with the “touchstone”

- = a stone that can be rubbed to measure its purity (trust, value)

>> to do: Phoenicians: created currency Representative Money: paper money = coin value Fiat money = backed by a promise only

weights and measures

writing

> create new page for writing

- power of writing

- from Jared Diamond's Guns, Germs & Steel", p 30:

Another chain of causation led from food production to writing, possibly the most important single invention of the last few thousand years (Chapter 12). Writing has evolved de novo only a few times in human history, in areas that had been the earliest sites of the rise of food production in their respective regions. All other societies that have become literate did so by the diffusion of writing systems or of the idea of writing from one of those few primary centers. Hence, for the student of world history, the phenomenon of writing is particularly useful for exploring another important constellation of causes: geography's effect on the ease with which ideas and inventions spread.

and, regarding his analysis of the Spanish conquest of the Inca, p. 81:

Why weren't the Incas the ones to invent guns and steel swords, to be mounted on animals as fearsome as horses, to bear diseases to which European lacked resistance, to develop oceangoing ships and advanced political organization, and to be able to draw on the experience of thousands of years of written history?

- from "An Inca Account of the Conquest of Peru" by the Incan prince, Titu Cusi (who learned and wrote the book in Spanish), on some of the first Incan encounters with the Spanish:

we have witnessed with our own eyes that they talk to white cloths by themselves and that they call some of us by our names without having been informed by anyone and only by looking into the sheets, which they hold in front of them.

Culture and Cultural & Technological Achievements

- deatils

- sources:

Other

Features of Civilization

Historical sources & methods

- tools and techniques to study history

types of historical evidence

- archeological evidence:

- remains (bones, fossilized human, animal, insect remains with DNA)

- carbon-material for dating

primary source

- historical evidence created by the historical actors or at the time

- i.e., contemporaneous = "of the time"

- eye-witness testimony

- contemporaneous interviews or accounts, such as:

- newspaper reports of eye-witness accounts

- diaries

- personal letters

- court testimony

- oral history

- interviewing someone about their personal experiences in the past

- may involve selective or inaccurate memory

- contemporaneous interviews or accounts, such as:

- other original documents, including:

- official papers

- newspapers

secondary source

- historical evidence created by non-participant observers

- could be contemporaneous or historical

- an "indirect witness" would be someone who lived at the time but did not directly participate in the event

- could be contemporaneous or historical

techniques to evaluate historical documents

- OPVL

- Origin

- Purpose

- Value

- Limitation

- HAPP-y

- Historical context

- Audience

- Purpose

- Point of view

- y = just to make the acronym "HAPPy" complete

Historiography

= the study of how history is studied

Historiographic schools

Bias in study or writing of history

- confirmation bias

- see Confirmation bias

- editorial bias

- hagiography

- biography that idealizes the subject

- from Greek for writing about saints

- political bias

- note: application of a particular historiographic techniques does not imply a bias

- although it could have bias in the work

- see Historiography section

archeology & other historical evidence

>> to do

Cognitive biases, effects & syndromes

Confirmation bias

- observer bias limits observations to expected or desired outcomes

- confirmation bias powerfully limits one's ability to see something from a different perspective and, therefore, to evaluate it effectively and accurately

- confirmation bias has significant effects in science, as many, even empirical, studies yield results that the investigators are looking for

- note that confirmation bias may also yield great insight, especially if that bias leads to a new or different perspective that others would not see

Dunning–Kruger effect

- the cognitive bias of overestimation of one's own competency and lack of awareness of one's own limited competence

- an error in self-awareness whereby a person cannot evaluate his or her own competency

- called "illusory superiority"

- the effect also shows that people of high ability tend to underestimate their own competence

- original study was entitled, "Why People Fail to Recognize Their Own Incompetence"

- "the miscalibration of the incompetent stems from an error about the self, whereas the miscalibration of the highly competent stems from an error about others."

- the authors later explained that the Dunning–Kruger effect "suggests that poor performers are not in a position to recognize the shortcomings in their performance"

- the Dunning-Kruger effect is observable but not provable

- i.e., it can happen but just because someone does not have competence does not mean that person will draw hasty, broad and wrong conclusions

Hawthorne effect / Observation bias

- also known as "observer effect"

- when the observer changes the actual event / object being observed

- example : typically checking the air pressure of an automobile tire requires letting some air out of it in order to place the pressure gauge on it to measure the air pressure

- the "Hawthorne effect" is named for a study at "Hawthorne Western Electric"

- conducted at the company electrical plant in Illinois, 1924-1927

- researchers studied the impact of lighting (illumination) on worker productivity

- however, the increases in worker productivity was not a result of the changes in lighting

- but due to the fact that the workers knew they were being observed

- which motivated them to work harder

Illusion of truth paradox

- in economics, consumers believe they have myriad choices, when in actuality their consumer choices have little distinction from one another and, worse, are owned by only a few conglomerates (large businesses with many branches)

Mediocrity paradox

- = the idea that conformity to inept, incompetent or corrupt systems

- = leads to individual advancement within those systems without changing or improving that system

- in fact, mediocre people do not want to change inept systems precisely because they benefit themselves

- = leads to individual advancement within those systems without changing or improving that system

- similar to the Peter principle, but explains why people are promoted above their competency

Narrative Fallacy

- a logical error of generality from a specific, in this case of a "narrative" or "story" that would seem to explain a certain outcome,

- yet, another who experienced that same "narrative" would not experience the same outcome

- from Nassim Talib

Newspaper paradox

- following the rule that when you see in the news an event or topic to which you have expertise or experience, the reporting on it will be incorrect, sometimes completely wrong

- however, we don't often apply that same level of inquiry or tests to news we see about things we do not know well or have experienced

- thus the paradox that we accept as true something reported that we know little about, all the while knowing that an expert on or direct witness to that news would know it is inaccurate.

- from Michael Bromley

Peter principle

- the idea that people within an organization tend to rise to their "level of competency"

- started as a satirical observation of how companies promote people

- the observation is largely accurate that people will be promoted to higher levels until they are no longer able to demonstrate competency at some level, and will therefore not be promoted again

- started as a satirical observation of how companies promote people

- the Peter Principle may help explain why historical actors rise and then become mediocre at their pinnacle

Political Framing

- a political message, policy, position, perspective or statement that is shaped and ultimately derived from that political point of view

- the "frame" is the perspective which shapes the content of the "picture", i.e. the topic, subject, or position

- the goal of the "frame" is to shape audience understanding by through emphasis and deemphasis of various elements of a topic

- i.e., if the topic is health care, the "frame" could be one the emphasizes cost, which deemphasizing quality

- the "frame" guides the audience to that "point of view"

- also called "spinning", which is to "spin" or redirect a negative into a positive

Rorschach test

- from the "Rorschach Inkblot Test"

- a controversial psychological / personality test developed by the Swiss psychoanalyst, Hermann Rorschach in 1921

- the idea of the test was to assess someone's personality based upon perceptions of "ambiguous designs"

- i.e., "blots" of ink on a paper

- the test was supposed to indicate a personality type or condition based upon response to the "Inkblot"

- for the Humanities (social sciences & literature), "Rorschach test" is a reference to a bias

- so a situation or idea can be used as a Rorschach test to indicate a certain line of thinking, outlook, or perspective on something

- i.e., "The current crime wave is a Rorschach test of people's views on policing."

- however, as with the original Inblot test, use of a Rorschach test in the humanities is itself biased

- so one must be careful in its application

Other/ todo

- alleged certainty fallacy

- attribution to experts fallacy

- unbroken leg fallacy

Other theories & conceptual tools

regression to the mean

Weber's "Protestant Work Ethic & the Spirit of Capitalism"

External Resources

Websites

- Prentice-Hall Social Studies Skills Tutor

- Trumbull County Educational Service Center Social Studies Tools with links organized according to Social Studies areas

- Reading Quest "Making Sense in Social Studies

Articles

See Also

- bulleted link to other related internal or web articles

- bulleted link to other related internal or web articles

Lesson Plans & Teaching Ideas

Sub Heading

- details

- details

- details

- details

- etc.

- sources:

Sub Heading

- details

- details

- details

- details

- etc.

- sources:

Other Student Projects and Investigations

- ideas for student work / engagement with the topic

Readings for students

- Active Reading

- apply Prior Knowledge as you read: "what do I already know about this?"

- identify New Knowledge about what you read: "oh, that!"

- develop questions about the New Knowledge as you read: "Okay, but what about...?"

- links and more ideas here

>> see SocialScience-EssentialSkills11.wpd

- Comparative Advantage exercise: Tuvulo & Nauru comparison

- Possible economic choices for Nauru and Tuvalu include:

- phosphates

- oceans/fishing

- tourism,

- .tv domain registrations (Tuvulu)

- technology

- foreign aid

- banking center

- leaving the island

- Questions:

- Is it advantageous for Nauru to produce phosphates?

- Is it advantageous for other countries to purchase phosphates from Nauru?

- it advantageous for Tuvalu to develop an Internet domain name?

- Is it advantageous for other countries to use that domain (.tv)

- What should Nauru have done instead of relying on phosphates?

- What would Tuvalu be giving up by relying on foreign aid?

- Possible economic choices for Nauru and Tuvalu include:

Logic

- todo

>synthesis: Hegelian dialectic: # The thesis is an intellectual proposition. # The antithesis is simply the negation of the thesis. # The synthesis solves the conflict between the thesis and antithesis by reconciling their common truths, and forming a new proposition. wiki: In classical philosophy, dialectic is an exchange of proposition (theses) and counter-propositions (antitheses) resulting in a synthesis of the opposing assertions, or at least a qualitative transformation in the direction of the dialogue. It is one of the three original liberal arts or trivium (the other members are rhetoric and grammar) in Western culture.

History jokes & jokes from history

- see also Geography jokes (s4s wiki)

Historical jokes

>> to do jokes from across history

History jokes

- "I have two cousins, Alsace and Lorraine."

- click EXPAND for the punchline:

- "They never did get along."

- A Roman walks into a bar and holds up two fingers and says...

- click EXPAND for the punchline:

- "Five beers please"

- Why is it called "Mesopotamia"?

- click EXPAND for the answer:

- Because there weren't just a lot of Potamians, there was a Mesopotamians!

- Why is it called the "Dark Ages"?

- click EXPAND for the answer:

- Because there were so many knights

- What music did the Pilgrims listen to?

- click EXPAND for the answer:

- Plymouth Rock

- What cut the Roman Empire in half?

- click EXPAND for the answer:

- A pair of Ceasars

- How did Vikings send secret messages? ?

- click EXPAND for the answer:

- By Norse Code

- How did Louis XIV feel after building Versailles?

- click EXPAND for the answer:

- Baroque

- What does Alexander the Great have in common with Kermit the Frog?

- click EXPAND for the answer:

- the same middle name, "The"

- Why was WWI so quick?

- click EXPAND for the answer:

- because they were Russian

- Why was WWII so long?

- click EXPAND for the answer:

- because they were Stalin

Soviet Union jokes

- A man in the Soviet Union saved up his money to buy a car. He went to the dealer and ordered the only car available.

- "Great," he said to the salesman, "When do I pick it up."

- "Oh," the salesman replied, "March 21st next year."

- "Okay," replied the man. "What time?"

- "What time?" asked the salesman. "It's not for a year and a half from now! Why do you care what time?"

- click EXPAND for the punchline:

- "You see," the man explained, "I have an appointment that morning w/ the plumber."

- A Russian man escaped the Soviet Union and came to America. His neighbor asked him what life was like back in Russia.

- Russian: “Oh, my old apartment was perfect. I could not complain.”

- American: "What about your job?"

- Russian: “Oh, my old job was perfect. I could not complain.”

- American: "Wow. What about the food?"

- Russian: “Oh, the food was perfect. I could not complain.”

- American: "Well, if everything was so great in the USSR, why'd you come here?"

- click EXPAND for the punchline:

- Russian: "Here I can complain."

other to do

- Anachronism

- Apocryphal

- Social Studies vocabulary list >> and add a category see pages for critical and analysis